The book we call the Bible was written over the space of hundreds of years. Given this huge span of time we’d expect to see change in the way language is used throughout its pages. And we do.

Across the three different types of Hebrew found in the Old Testament[1] we can see words falling out of favour for other words describing the same thing. We are familiar with this concept in English, e.g. a few decades ago people listened to the “wireless,” yet, today, people listen to the “radio.” Same thing, different word – language nerds call this “lexical change.” The same happens in the Bible. In fact, scripture explains to us that this is the case. Here’s an example.

In the early chapters of Samuel we find Saul wandering the hills of Samaria looking for his father’s lost donkeys. At the point of giving up, the boy accompanying Saul suggests they go ask Samuel where the donkeys are.

1 Sa 9:11–12 As they went up the hill to the town, they met some girls coming out to draw water, and said to them, “Is the seer here?” They answered, “Yes, there he is just ahead of you…”[2]

The boy expects Samuel to be able to divine where the donkeys have wandered off to, because he’d heard that Samuel was a seer.

When we hear the word seer today, images may be conjured up of clairvoyants using extra-sensory perception to “see” things that others cannot. When we read verse 9 we find that whoever was responsible for the final form of the book of Samuel didn’t expect his audience to understand the relevant Hebrew word:

1 Sa 9:9 (Formerly in Israel, anyone who went to inquire of God would say, “Come, let us go to the seer”; for the one who is now called a prophet was formerly called a seer.)

The above verse is a later edit to a more ancient form of the text[3] warning the reader about a word they’re just about to stumble over. The editor explains what the word means, and gives an example of how it was used “back in the day.” The edit would only have been added because it was necessary – the editor’s readers wouldn’t have understood the passage without the explanation.

A verse in Isaiah provides a fascinating snapshot of a time when both terms were still in use:

Is 30:9–11 For they are a rebellious people, faithless children, children who will not hear the instruction of the LORD; who say to the seers, “Do not see”; and to the prophets, “Do not prophesy to us what is right; speak to us smooth things, prophesy illusions, leave the way, turn aside from the path, let us hear no more about the Holy One of Israel.”

The terms “seer” and “prophet” are used in a parallelism, i.e. where two phrases in sequence refer to the same thing. At the time that Isaiah 30 was written it seems that both “seer” and “prophet” were known and used interchangeably.[4]

Knowing that “seer” fell out of use and was replaced by “prophet” is helpful when trying to work out what sources the Chronicler used when composing his history of Israel. The Chronicler wrote very late in the history of the Old Testament text[5], so we’d expect not to find the word ‘seer’ in the text. However, he does use “seer” so it’s possible that he’s quoting an ancient source:

1 Ch 9:22 All these, who were chosen as gatekeepers at the thresholds, were two hundred twelve. They were enrolled by genealogies in their villages. David and the seer Samuel established them in their office of trust.

We find the same thing in 1 Chronicles 26:28, 29:29, 2 Chronicles 16:7, and 16:10. The Chronicler may have worked with sources dated to before the time when “prophet” replaced “seer”.[6]

You’re probably wondering why we’re explaining the obvious – of course language changes over time. Of course words fall out of favour and other words are used instead – that’s our experience; we know that’s how language works. We don’t need any language qualifications to know that this is obvious stuff. So, why bother explaining it?

“…the purpose of the notice is to explain an outmoded term that might be confusing to his audience.”[7]

When it comes to the Bible, it appears that we sometimes forget that language use changes over time. We forget that Biblical Hebrew and Koine Greek were once living languages. A common way of attempting to understand a passage is to identify its key words, search for every instance of those words (often the “root” form of the word) and observe how the words are used across the biblical books.[8] However, given what we’ve covered above it should be obvious that this is a flawed approach when not performed with caution.

For example, if we wanted to look up every passage that mentioned a prophet, but only searched for the Strongs number for the word “prophet”, it goes without saying that such a search would not turn up every reference to a prophet, because the word seer was not searched for. We’d be dealing with an incomplete result set.

Here’s the important point: Words are labels for things, and over time, though the things they refer to don’t change, the labels for them can and do change. “Seer” and “prophet” were both labels for the same thing. Samuel remained Samuel, but the word used to describe him did not. So, searching for the label may not turn up all instances of the thing we’re looking for. To do that, we need to search for instances of the thing. How do we do that if the thing has many labels?

We search for passages that make mention of the semantic domain.

A semantic domain is the collection of labels that point to a thing. Both “prophet” and “seer” are members of the semantic domain of “prophet”.

In the same way that Mr Strong indexed every word in the Bible[9], others have created lexicons of semantic domains. Here are two:

- Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament based on Semantic Domains

- Dictionary of Biblical Languages with Semantic Domains (Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek)

A third option is the Bible Sense Lexicon feature of the Logos Bible software. And with that, it’s time for a tangent…

To search for all instances of a semantic domain in Logos, simply open the passage in question, select the relevant word (e.g. ‘prophet’ in verse 9), take a look at the sense of the word in the inline interlinear, and click on it to look it up in the Sense Lexicon.

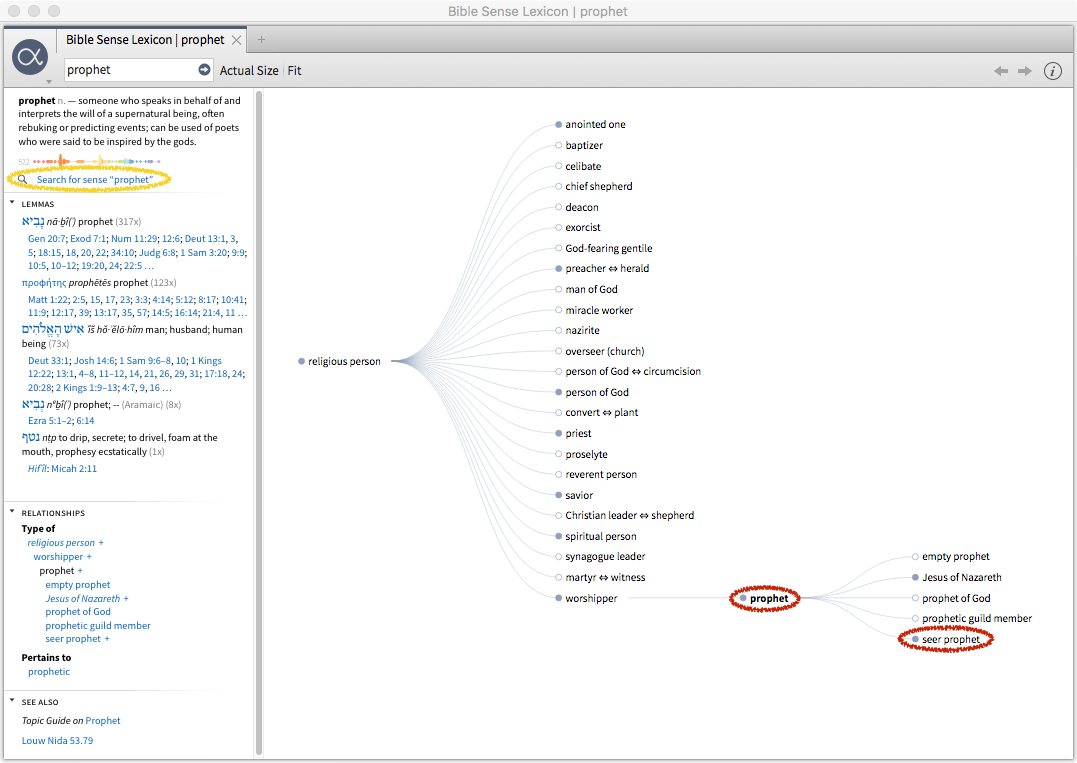

In the right hand side of the following Sense Lexicon screenshot you’ll notice that “seer prophet” is filed under “prophet” (both highlighted). This makes life simple in that a search for any word with the sense of “prophet” (click on ‘Search for sense “prophet”’ highlighted in yellow) will find both “prophet”, and anything filed under it, including “seer prophet”.

Here’s the result of searching the Bible for instances of the semantic domain of “prophet”:

Notice that the search contains both “prophet” and “seer”. In fact, it contains a number of other results, e.g. prophetess, Man of God, and holy man of God. All those passages are speaking about someone acting in the capacity of a prophet though using different language to refer to them.

A simple search for the Hebrew word/Strongs number behind the word for “prophet” wouldn’t have turned up every passage where a prophet is mentioned.

Returning from our software-related tangent it is clear that searching for words, thinking that doing so is enough to locate all relevant passages on a particular topic, is not going to give you what you want. Doing so is based on a misunderstanding of how language works. A friend, with his tongue only half in his cheek, has said that “the most useful language for Bible study is Spanish.” His reasoning is that fluency in a second language provides insight into how language works; and that that insight acts as a corrective against treating other languages in ways that don’t make sense.

What happens in English and Spanish happened to Biblical Hebrew and Koine Greek when they were living languages – words fell out of favour for other words, and other words changed meaning. We would do well to bear that in mind when searching for related passages. Don’t focus on words at the expense of senses.

Footnotes

- See Phillip Marshall, “Hebrew Language,” ed. John D. Barry, David Bomar, et al., The Lexham Bible Dictionary (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016).

- All scripture quotes from The Holy Bible: New Revised Standard Version (Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1989)

- See Ralph W. Klein, 1 Samuel (vol. 10; Word Biblical Commentary; Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1998), 87.

- This indicates that the final form of the book of Samuel only came together after the time of Isaiah, but that’s a story for another day.

- Chronicles tells the story of what happened after the return from Babylon so it can’t have been written before then.

- Other explanations are possible.

- P. Kyle McCarter Jr., I Samuel: A New Translation with Introduction, Notes and Commentary (vol. 8; Anchor Yale Bible; New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2008), 177.

- This itself is a mistake when the search is performed with too broad a scope, however that’s another story for yet another day.

- A gross oversimplification

Author: Nat R